In her recent autobiography the renowned editor Gwen Lister for the first time disclosed the closely guarded secret of how and where she obtained the initial funding to start The Namibian newspaper. It is a small but important historical detail that has remained hidden from public view for decades.

In Chapter 6 of her 2021 autobiography, Comrade Editor, Lister for the first time publicly mentioned that after she had met Sam Nujoma, the leader of Swapo in exile, in France in 1981, she had traveled to Lusaka, Zambia in mid-1984 — ostensibly to attend the Zambian Independence celebrations — where she also met up with him.

According to Lister’s account, she told the Swapo leader that she wanted to start a newspaper to support the struggle for Namibian independence, and recalls that he excused himself for a while and went into a room, returning shortly afterwards with a bag full of cash, which he handed to her, which she was to use to start her newspaper.

Aware of the risks of returning to Windhoek with a bag full of cash, she met with Nujoma’s brother-in-law, Aaron Mushimba, in Lusaka the next day to ask him to transfer the money to her from a London account, which he did.

So far, so good.

The problem though is that by 1984 the Swapo leadership had begun to detain its young cadre who were demanding food and clothes, as well as internal democracy and transparency. This period of internal strife and suppression in Zambia and Angola in the 70’s and throughout the 1980s was documented in great detail by the late Lutheran cleric, Rev Samson Ndeikwila, in his autobiography, Agony of Truth.

The abuses in the camps also came to light during hearings in 1982 before the US Senate as part of the Denton Commission’s inquiry into the role of the Soviet Union in southern Africa, where former Swapo cadre testified to having been subjected to torture and wrongful imprisonment by the leadership in exile, but it remains an open question to what extent journalists on The Namibian editorial team were aware of these documented human rights violations against Namibians in exile at the time.

As is well known, The Namibian started as a weekly in 1985 and soon rose to prominence for their courageous reporting on the brutality of the occupying South African forces in Namibia, which is surely commendable, but the problem is that while Swapo was detaining many of its cadre without trial in Angola throughout the 1980s The Namibian newspaper apparently hid this pertinent fact from their readers until after the surviving detainees at Lubango were released from the dungeons under the watch of UN observers and international reporters in May 1989.

Even by mid-1989 when the crimes of Swapo against its cadre had become an established fact, to the extent that The Namibian was compelled to report on it, Lister did not address the abuse, rape, torture and disappearance of women and men in the Swapo camps in her editorial or ‘Political Perspective’ column. The story, which made headlines internationally, was tucked away on page 3 of the Friday edition.

Exposure as deterrence

For context, it is worth noting that in the paper’s 25th Anniversary Supplement, former board member Advocate Dave Smuts said the newspaper had played a crucial role in curbing the abuses of the South African government in Namibia through its fearless reporting and by cataloging the abuses. He argued that, “the steps taken against abuse in The Namibian and in court” had a deterrent effect:

“I believe that the repeated exposure of abuses in court proceedings and in The Namibian … had an increasingly powerful deterrent effect upon security force action and made an important difference to many people's lives. It also served to galvanize large sections of the population against these repeated and persistent abuses and about the importance of protecting human rights.”

He goes on to say:

“A single example of exposure illustrates the point. Many readers will recall the court application to secure the release of several people who were detained for more than six years without trial after being captured in Angola in the course of the Cassinga raid in 1978 and brought back to Namibia. We did not succeed with that application in the courts. But the international indignation, spurred on by our churches and their leadership, which resulted from its exposure, meant that upon the eve of the hearing several detainees were released. International condemnation continued around the issue until the remaining detainees were released a few months later. The infamous detention centre where they were held near Mariental soon became something of the past.”

(The 25th Anniversary Magazine of The Namibian, Pp. 15-17)

Smuts went on to praise the paper for its “courageous reporting” as “It also meant that — as instances of abuse occurred and received wider coverage — others felt encouraged to come forward and seek redress for and to expose the abuses which were perpetrated upon them. The courageous reporting of these abuses made a massive difference.”

In his view, the reporting by The Namibian on the abuse of detainees by South Africa helped bring such abuses to the world’s attention and thus helped to end them, which begs the question of what impact the newspaper’s total silence about the torture, detention without trial and disappearance of Namibian fighters in the Swapo camps had on the continuation of such abuses throughout the 1980s.

Given the observations of Smuts about the deterrent effect of reporting on human rights abuses, it also remains an open question what impact reporting on the plight of Namibian detainees in exile would have had on the political consciousness and choices of the general public if they had been duly informed by the most popular — by then daily — paper, about what was happening to their children in exile.

Source of the start-up funds

Lister in her autobiography did not specify how much money Nujoma gave her in Zambia, nor did she report on any questions she might have had about the source of the money, but as noted by the authors of Searchlight South Africa, the Swapo leaders in Zambia were suspected by the youth of selling goods provided by solidarity groups abroad, and pocketing the proceeds.

According to Sue Armstrong in a biography published in December 1989 on the life of Andreas Shipanga, one of the founding members of Swapo, he said that in Zambia he soon found himself in conflict with the leadership after young fighters had turned to him for support as a longstanding leader of the movement.

Armstrong reported in her book, In Search of Freedom: The Andreas Shipanga Story, that he also accused Peter Mueshihange, who would later become minister of defense in independent Namibia, of “working rackets” in Lusaka with Nujoma and Peter Nanyemba. Shipanga claimed that,

“Nanyemba was very shrewd. He had little formal education, but he was clever. He lived liked a warlord, womanizing and spending money freely. He had many business interests: he was in partnership with Nujoma and Mueshihange in two nightclubs in Lusaka—the Kilimanjaro and the Lagodara. One of Nanyemba's tricks was to order supplies from the biggest chemist shop in Lusaka and to get one of our supporting governments or groups to settle the bill. Next day the goods were on sale in the Second Class Market... Nanyemba simply pocketed the proceeds. All this was well known in Lusaka, and there were even jokes about how blankets given by Swedish anti-apartheid groups were making the leaders of Swapo rich.”

(Searchlight South Africa, Vol 2, No 2, January 1991, p.44)

The distrust between the leadership and rank-and-file, however, was not something new. As Searchlight SA noted,“In a memorandum to the Swapo leadership drawn up at the SYL [Swapo Youth League]'s headquarters in Lusaka on 26 February 1975, the Youth Leaguers in Zambia expressed 'fear' over the relationship between themselves and 'the comrades who have been here before us', noting 'a gap between us... a result of mistrust or suspicion'. Whenever they asked about something, the memorandum continued, ‘we are accused of being 1) reactionaries; 2) destroyers of the party; 3) and that we are fighting for power.’” (Genesis of the ‘Spy Drama’ Part II, p.43-44.)

As reporter Paul Trewhela concluded, “The psychology of the Swapo leaders against their internal critics is summed up here. This political mind-set, more than anything else, produced the purges of 1984-89. Against this ingrained suspicion, the SYL demanded full internal democracy within their organization. Their standpoint was emphatic and eloquent: ‘We deserve every right to ask where we do not understand and to contribute wherever necessary.'“

Trewhela, the author of Inside Quatro: Uncovering the Exile History of the ANC and SWAPO, reported that, “The [SYL] letter noted that there were times when members in Swapo camps in Zambia did not have food, some were without clothes and there were severe problems with transport, while at the same time party cars were 'used as individual properties' by leaders. 'Leaders must be good examples', demanded the SYL, noting that at almost every meeting up to that time the reverse had been the case, leading to 'a spirit of fear among the members towards our leaders.'”

In light of these developments, it seems hard to believe that even by 1985, Lister and reporters at The Namibian were unaware of the struggles of the Namibian youth in exile and did not ask about the source of the start-up funds they received. At any rate, they certainly never reported on this funding until Lister disclosed it in her book.

I asked the now retired editor after her autobiography was published whether the startup funds provided by Nujoma influenced her decision not to report on the detention without trial, torture and disappearance of Namibian fighters in exile, but she was not able to answer at the time as she said she was attending a workshop.

‘Paid agents’

The case of Rudolf Kisting, a Swapo Youth League member in Namibia in the 1970s, who later went into exile, is highly instructive. According to Searchlight SA, Kisting after returning from his studies in the Soviet Union met Nujoma for a meal in Harare in the 1980s, where the Swapo leader urged him to assist the organization in Angola.

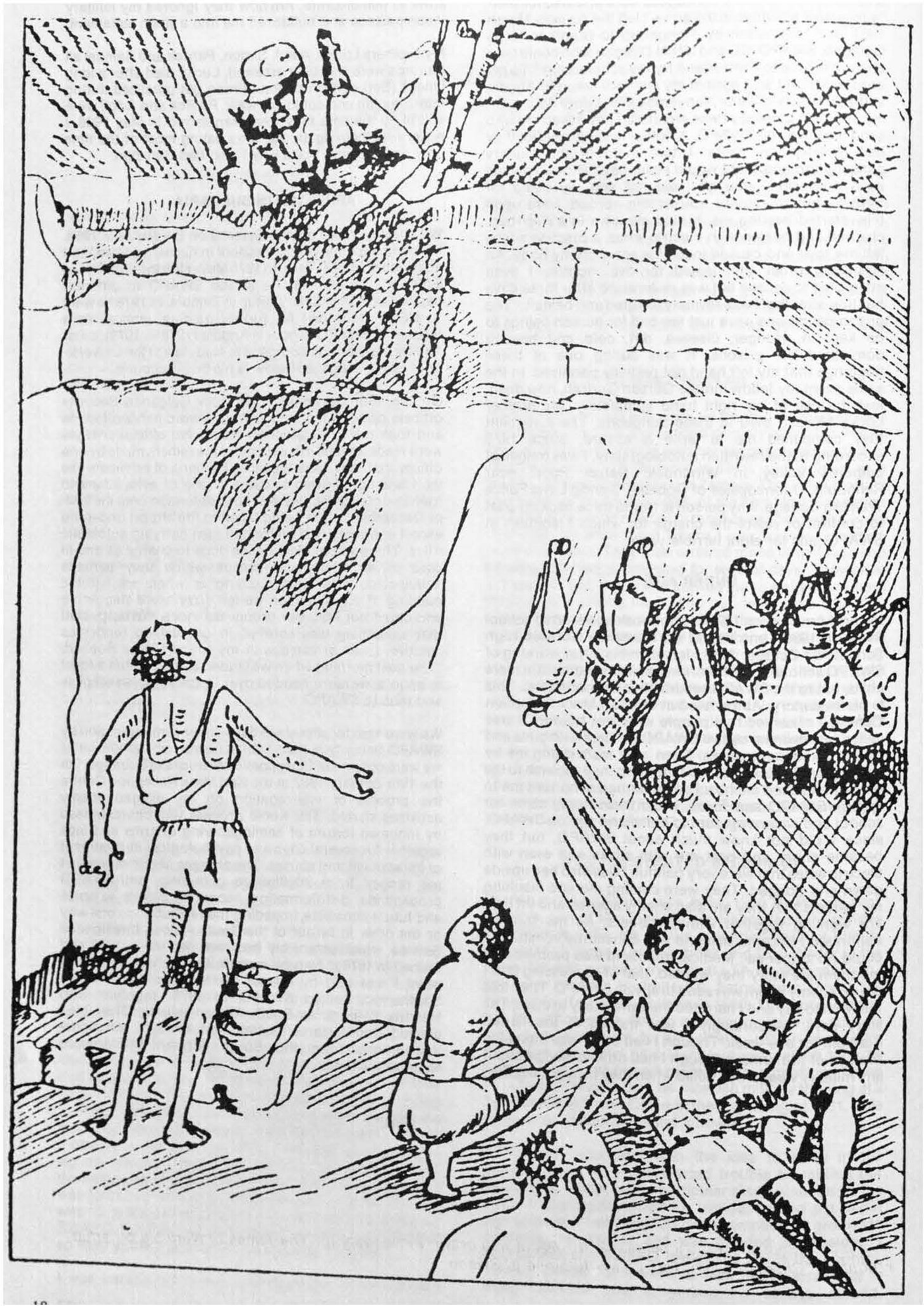

“This was Kisting's intention in any case. He then flew to Luanda in the company of one of Nujoma's bodyguards, who had been present at the meal, and was arrested by Swapo security very shortly afterwards. After torture and years in the pits in southern Angola, he was released last year [1989] along with other recipients of President Nujoma's hospitality.” This was confirmed by Dr Sophie Kisting, Rudolph’s sister, who was present at the meeting in Harare. (See Genesis of the Spy Drama, p 57)

The editors of Searchlight SA noted that a similar fate befell Kavee Hambira, who had been working for Swapo’s radio service in Luanda. They cited Hambira’s affidavit submitted to the High Court in Windhoek in September 1989, shortly after his release, in which he recounted that:

“In May 1984, I was told by Mr Hidipo Hamutenya that I was to fulfil an assignment for approximately one week in Lubango. I flew from Luanda to Lubango. When I arrived at the airport the chief of security of Swapo, Solomon Hauala, met me and he immediately arrested me. (Spy Drama, Part II, p 57)

He was “tortured on a daily basis for ten days and imprisoned in the pits for five years, during which time he said Hauala and Hamutenya personally forced detainees to make false confessions on video. Hambira was eventually released with many other detainees in May 1989.”

(Call Them Spies: The Namibian Spy Drama, Ben Motinga, Nico Basson, 1989, p 176)

Hamutenya was part of Swapo’s inner circle in exile as a member of the politburo and information secretary in the 1980s. He also became minister for information and broadcasting after 1989, while Hauala — who was labelled by the ex-detainees as ‘The Butcher of Lubango’ — was appointed head of the Namibian army.

In her interview with Hamutenya in early 1989, for the first time on record Lister asked about the rumours regarding the detainees, whom she referred to as “the Swapo 100”. Her question, though, strongly implied that those — mainly socialists and human rights activists — who were seeking to expose Swapo’s treatment of its members in exile were likely working in support of South Africa:

“It would seem in the future, that pro-South African forces will use ‘left-wing tactics’, rather than ‘right-wing’ to try and undermine the Swapo movement. Some see reactionary elements in the guise of Marxism/Trotskyism. There was also talk at the time of the arrest of the ‘Swapo 100’ that the alleged spies had been trained in Marxism/Leninism before they left the country. Can you comment on this?”

From this we may infer that the editor was aware of the detainee issue. In his response, Hamutenya latched onto the idea that those fighting for the detainees’ release were likely paid agents of South Africa, for he said: “It is quite conceivable that paid agents of the apartheid regime will seek to disguise their treacherous activities, designed to undermine the liberation struggle, through Marxist-Leninist posturing.”

Although I have no personal animosity towards Gwen Lister and recognize her contributions in other respects, I must agree with Trotsky on this point, that although friendship is valuable, the truth is more important.

As I reported previously after studying all the editions of The Namibian published up to the end of 1989, besides that one interview no further questions were ever placed on record again by The Namibian about the fate of the hundreds of youth held without trial in holes in the ground in exile — until their eventual release in May 1989.

Numerous cases

There were many such cases of imprisonment without trial on trumped-up charges, of torture, rape, abduction and forced disappearances.

(‘Spy Drama’ Part II, pp 57-58, and The 1976 Anti-Corruption Rebellion, p.16).

Some of these were documented by late Lutheran Pastor Siegfried Groth in his belated book, Namibia — The Wall of Silence: the Dark Days of the Liberation Struggle, published in 1995, which brought to light the personal testimony and letters of detainees and others in the camps, where he had served as chaplain to the fighters in exile. In it, he also asked forgiveness and acknowledged the long-held silence of the Lutheran Church on this issue, which late Rev Ndeikwila wanted the Church to address.

But the Church was not alone in suppressing these horrific historical facts.

In breaking the silence on this painful issue, Searchlight SA also reported, among others, on the cases of Tauno Hatuikulipi, a member of the central committee and military council, who died in a Swapo prison in Angola in 1984, after he was accused of being a South African spy, as well as Lucas Stephanus, who “was killed by Swapo in Lusaka the same year, and his body never found.”

“Eric Biwa, also on the central committee and [later] a representative of the Patriotic Unity Movement (PUM)… was deported from Cuba to Angola by plane in 1984 with one leg in a plaster cast, detained on arrival and kept for five years in pits in the ground. Benedictus Boois, also on the central committee, suffered the same fate.

“The vice secretary of the Walvis Bay congress, Othniel Kaakunga, subsequently a member of the Swapo politburo, went into exile and was then tortured and detained for three years, two of them in solitary confinement.”

The editors at Searchlight SA concluded that from the 1970s onwards, Swapo’s security apparatus “took on the character of witch-finder general, the grand inquisitor for whom even the slightest sign of mental independence was threatening.”

It was in these troubled times that the young UCT graduate and seemingly naive and idealistic reporter met with Nujoma in Lusaka in 1984, where Lister by her own account accepted money from him to start her newspaper. It is unclear though whether or to what extent Lister was aware of the goings-on within the movement, or whether she asked about the actual source of the funds that she received.

It is a well-documented fact, though, that the young fighters in Zambia were complaining at the time of hunger and deprivation, as well as corruption among the party leaders, and that they sought greater internal democracy, which resulted in the detention and disappearance of many, with the active support of the Zambian government, in what later became known as the “Shipanga Affair.”

Despite her reluctance to investigate and report on the torture and unlawful detention of the Namibian fighters in exile, in September 1988 Lister was awarded the IPS International Journalism Award at the UN in New York, and the Pringle Prize for Journalism by the South African Society of Journalists, as well as an award from the Committee to Protect Journalists in New York in 1991. In 2000 she was named as one of the 50 Press Freedom Heroes of the past half-century by the International Press Institute, and in 2004 was awarded the Courage in Journalism Award from the International Women’s Media Foundation in the United States.

For further reading:

Raped on Arrival: The Story of Claudia Namises and the Swapo camps

In Depth: How the press covered up the abuse of women fighters in exile